Reports and Articles

Our projects explore different ways that people at the local level can influence conversations and policy making at the highest levels in Africa.

Web Administrator

Anatomy of Corruption

Corruption is a challenge to democracy. The anti-corruption organization, Transparency International define the phenomenon of corruption as ‘the misuse of entrusted power for private benefit.’ Corruption is generally “an activity which undermines public confidence in the integrity of the rules, systems and institutions that govern society is corrupt”.

In poorer and developing countries where corruption is structural, pervasive and endemic, and despite its harmful impact on “good governance,” “sustainable development,” and “human justice,” it is considered to be something of a natural order.

It is the way things are done in the conduct of business and governance, “habitualized” and “institutionalized” into the social fabric, rationalized and justified. Reasons to fight it or oppose it are weakly internalized so as to sustain any significant counter collective action.

In fact corruption undermines the very idea of citizen and citizenship, and it is much in this light that presumed 'citizens' in states pervaded by such a phenomenon see themselves – as mere ‘inhabitants’ rather than as citizens. Yet the system continues to self-reproduce until “conducting personal and public affairs eventually collapses” and as “rottenness” strikes at the core, society and the State are rendered “incapable of facing major outside challenges. Then, the price is very high in terms of uncertainty, loss of trust, and risky supersession at best– and civil unrest, revolt, and bloody revolution at worst”.

From the citizen perspective, control of corruption is always a significant question. The instruments of controlling corruption are both direct and indirect for citizens. At least in theory, the more direct the channels of influence are, the stronger the citizens’ role is in the control of corruption.

Corruption is seen as a primary threat to open and transparent governance, sustainable economic development, the democratic process, and business practices. Corruption is a multi-faced phenomenon, linking multiple issues together such as abuse of entrusted power for private gains, low integrity, taking bribes, maladministration, fraud, and nepotism. The big question is how to prevent the increase of administrative corruption in a single country? How to get a grip on the control of corruption in a singlecase study and how to properly identify the most important implications of corruption?

The proper diagnosis of the causes and logic behind corruption play an important role in combating it. The fact is that researchers will never be able to reveal all corruption to the public. Corruptio is an iceberg, in which only the tip can be seen and only known facts can be taken into consideration.

Old boy networks and nepotism are examples of such subtle unethical structures of pay-offs. Other manifestations and forms of corruption are of course not so subtle and much more sinister and destructive of the entire integrity structure of society.

Under such conditions of pervasiveness citizens may accept and participate in corruption, even when conscious of the error of their ways.

This constitutes a “social dilemma”, where despite the fact that citizens do understand the situation and the disastrous consequences of their own attitudes, they are unable or continue to be unwilling to do anything about it

Through a continuous process of ‘denial’ they may condemn corruption verbally but resist attempts at breaking its networks as many adapt to its order of things. In other instances, political allegiances in modern democracies filter perceptions or negative attitudes toward corruption depending on whether a group of citizens supports the government or not.

Governments all over the world and international organizations have designed strategies to fight corruption. In most cases the same government will bring a policy on corruption immediately after being implicated.

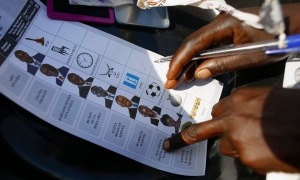

Election Observation and Monitoring

Elections are the cornerstone of creating a democratic political system. As such, monitoring can assist democratic consolidation by instilling domestic and international legitimacy.

Credible election observers play a key role in shaping perceptions about the quality and legitimacy of electoral processes.

Election observation missions start long before election day, with experts and long-term observers analyzing election laws, assessing voter education and registration, and evaluating fairness in campaigns. On election day, observers assess the casting and counting of ballots. In the days and weeks after the election, observers monitor the tabulation process, electoral dispute resolution, and the publication of final results.

Top Effective Election Observation Methodologies Used Around The World

Editor’s Note: This article is an extension of a previous one titled how to organize an election observation mission. The purpose is to provide further guidance on election observation missions by discussing some of the election observation methodologies used around the world to help new observation groups or existing ones know the sort of options available to them and the key players in each of the respective methodology for ease of technical assistance.

Election observation by its very nature is an effort towards ensuring the credibility of an election. This is done by deploying and watching the processes in order to deter possible fraud as well as ensure compliance with the regulations for conduct of election. The mere presence of accredited observers is capable of achieving transparency of the process. Different groups adopt different election observation methodologies in deploying observers based on their objective for such election.

There are several election observation methodologies and approaches that different election observation missions adapt and adopt in every given context. Advances in technology in the 21st century have further refined election observation methodologies. And given the very important place of democratic governance birthed through democratic election in human societies, innovative citizen election observation has definitely come to stay. Whilst every election poses its unique challenge, demanding a matching unique observation approach, knowing the various approaches being deployed around the world helps in the choice of methodology to adapt when and where.

Find below some of the election observation methodologies that are currently deployed around the world;

#1. Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT) also Known as Quick Count:

This is gold standard election observation methodology that has been around for thirty years. Adopted and adapted around the world with various branding such as Quick Count, swift count or rapid count, it all falls within the purview of systematic election observation. PVT or Quick Count is an election observation methodology that heavily uses information communication technology – ICT and science of statistics in deployment of observers.

The observers are deployed to pre-assigned polling stations after a random representative sample of the polling stations is drawn by a trained statistician. The observers are equipped with a checklist that cover all aspects of the Election Day process including official results at polling station levels. The checklist is what guide their observation and using their mobile telephones, the observers either call-in or text their observation reports routinely throughout the course of the election Day. The sent reports are bridged into sophisticated database that rapidly processes huge amount of data in real time.

This election observation methodology is mostly suitable in democracies that have history of flawed election often resulting into violence and are trailed by loads of litigations. And because this methodology is driven by data, it offers a perfect credible option to violence and can serve as good evidence in a litigation. With the use of ICTs, Quick Counts has the unique advantage of providing overall update on the entire election in real time on an election day. This has the ability to shape the right perceptions in the citizenry about the election.

Going down the history lane, PVT was first deployed by citizen groups in the Philippines in 1986, it has gained popularity and has been adopted in many countries around the world. It is about the most sophisticated, complex and technical election observation methodology as it upholds precision above and beyond. That is why expertise of Quick Count has remained limited with a select number of organizations like National Democratic Institute (NDI) in the USA, Transition Monitoring Group (TMG) in Nigeria, Centre for Democratic Development (CDD) in Ghana, Election Observation Group (ELOG) in Kenya amongst others.

Quick Count is hinged on use of Statistics, ICTs and thorough training and retraining for the many observer volunteers. Though expensive to deploy, it is about the only election observation methodology that provides independent verification of the official results announced by the Election Management Body-EMB. It also parallels the EMB in documentation of elections which can serve various purposes ranging from academic research to civic interventions based on empirical evidence. This election observation methodology is strictly an Election Day methodology and uses the stationary observer model with few roving supervisory observers. Quick Counts can also be adapted to observing referendums and other similar undertakings. See the PVT observation findings report for Nigeria 2011 general election.

#2. Hotspot Deployment or flash points observation

This is the election observation methodology that focuses on deploying observers to areas that are volatile in the leadup to the election or have a history of election violence. The objective is always to deter further outbreak of violence with presence of observers who are also on the lookout for the causes of the violence. The clue is that once under watch, human beings are likely to tame their excesses. Though the hotspot observers are deployed to observe the entire election process, their primary focus is to watch for violent outbreak indicators and report same immediately to enable authorities contain the situation.

This methodology has an inherent risk in that it places observers in potential violent zones. The plan is to not bring them to harm’s way but to leverage their presence in creating early warning systems that ensure such violence does not breakout and where unavoidable, have less casualties. Such observers are trained on safety drills and precautionary measure in addition to violent indicators monitoring and election processes.

Given the very dicey nature of this observation, it employs information communication technology for rapid and real time communication. Basically, the decision on where to deploy observers under this methodology is based on electoral history of the country, state or county as it relates to electoral security from previous elections. This methodology works both for election day as well as pre-election long term observation. For election day, it employs stationary observer model while in the pre-election period it is a roving observer model. Any group deploying with this methodology has to build very structured engagement with the security agencies. Here’s a very useful guide on monitoring and mitigation of electoral violence by National Democratic Institute for organizations looking to organize hotspot observation deployment.

#3. Traditional or general observation:

This is about the most known and probably the most used of all election observation methodologies. The core of this methodology is in deploying vast number of observers to create massive presence in as many polling stations as possible. Traditionally, it used to be just about the visibility of the observers around polling stations to deter saboteurs from rigging or manipulating the elections. This has changed for some observer groups as the methodology is now also leveraging ICTs; especially Social media to increase its impact around election reporting as well.

This methodology does not apply systematic deployment in managing observers neither does it build sophisticated reporting protocols on election day. Due to the large number of observers some missions deploy, it becomes also less likely to train and retrain the observers. Most missions hold observer briefings which basically tend to explain how the checklist can be completed on election day. Under this approach, observers are deployed to polling stations that are most convenient to them.

The deploying group only gets them accredited, holds observer briefing, equips them with a checklist and probably gives them a stipend at the end of the observation after they return the completed checklist. Though such data is anecdotal and may not offer an overall picture, it certainly has its impact in terms of shaping perceptions and giving citizens the opportunity to participate. CDD is a key player in this respect.

#4. Exit poll

This observation methodology is closely linked to opinion poll except that its conducted at polling stations and with participants being those who have cast a ballot. Mostly used in elections that are seemingly a close call, exit poll is the rarest observation methodology citizens deploy. The core of the methodology is to establish voter motivation for voting the way they do. Observers under this methodology station at one polling unit and depending on the sampling ratio; asks the picked voters after they cast their ballot who they voted and why they voted for the party or candidate.

This is also a very technical methodology that requires a lot of expertise in managing. Though it does not document votes share at the polling station level, the majority opinion in favour of a candidate or party usually bear a likelihood of such candidate emerging winner in that election. Exit polls do not concern itself with routine updates in the cause of the election day but do ensures adequate documentation of all respondents and responses either on paper or with dedicated electronic interphase. At the earliest possible time after close of polls, an exit poll can share its findings.

Being a technical methodology, training and sophisticated data analysis applications are essential. And exit poll is strictly an election day methodology as it only seeks to know the voters motive after balloting. See an account of 2015 UK Exit Poll Election.

#5. Targeted observation

As an emerging election observation methodology, it extensively borrows from Hotspot election observation methodology, but with focus on special populations or groups. With the increasing agitation for inclusive democracies, many populations that hitherto were not sufficiently catered for. Currently, four groups are covered in targeted observations:

- Women participation: With the increasing push for more women inclusion in leadership as well as gender mainstreaming in all spheres of human endeavour, women participation in election has become a key target. Observers group with special focus on women participation deploy observers with checklists that principally tracks how many women were polling officials, party agents, voters and candidates. The objective is to ascertain the level of women participation and to follow up with more advocacy. Organizations like the Women Trust Fund are leading the charge in encouraging more women participation.

- Youth participation: Another population that is increasingly getting all the attention in terms of participation in election is the youth constituency. Election observation deployment around this population as groups like YIAGA are undertaking with the youth observatory initiative is quite handy here. Observation for this group seeks to establish how many poll officials are youth, how many observers are youth and how many party agents and candidates are of the youth constituency. Again, the goal is to establish evidence for more advocacy.

- Security observation: This is yet another constituency that is getting specialized election observation attention especially around Africa given the unique security challenges at elections. Under this targeted observation, observers are deployed to specifically lookout for the conduct of the security personnel deployed as well as their performance. The idea was born of the fact that some overzealous security officers were beginning to abuse their duties, act partisan or under perform their duties. Groups like Cleen Foundation are doing so much around this kind of election observation.

- Persons with disability-PWDs: As a population that is short changed in more than one way, targeted election observation is beginning to focus on PWDs in order to principally lookout how polling units and voting processes are made accessible for this constituency. Advocacy is to see more PWDs run for office as well as function in all aspects of the electoral process. Observation here monitors all these and base further advocacies on gaps observed. Joint National Association of Persons with Disability is one of such group in Nigeria that is doing so much in this regard.

All election observation methodologies aim to ensure credibility of the electoral process. Though they vary in size and methods, the deployed accredited observers function on behalf of the citizens as such must be seen and perceived to be non-partisan for their reports to be accepted. Before you decide on which of the election observation methodologies your observation mission will adapt, it is very important to first define and establish what it is you want to achieve with the deployment.

The objective of the observation is very instrumental in the determination of which of the election observation methodologies is appropriate. Find OSCE Election Observation Handbook for more guides on election observation. Finally, knowledge of the legal framework and other national laws guiding the conduct of election in any given country is very important. Though general election observers code of conduct exists, every country still has her legal framework which also influence election observation missions. This can be in the area of observers’ accreditation, kits, checklist or movement on election day.

Africa’s 2019 elections: Democracy is a work in progress

Democracy in Africa was long regarded as an oxymoron. In 1990, there were just eight formal democracies out of the (then) 53 nations on the continent. Six years later, in 1996, 18 countries were classified as formal democracies. Democracy is now on the march throughout the continent with 23 countries holding elections at various levels in 2019 – and that presents unique challenges to a range of state and non-state agencies.

It’s a busy year for democracy in Africa, with 23 presidential, parliamentary and council elections in 2019. This reflects that elections have become an integral part of the continent’s democratisation process since the “Third Wave of Democratisation” in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

There have already been three elections – in Nigeria (general), Senegal (presidential) and Guinea-Bissau (legislative). The challenge to ensure elections are characterised by inclusiveness, transparency, accountability, and competitiveness will be further shaped by the remaining twenty elections, including South Africa, Malawi, Senegal, Mali, Ghana and Tunisia.

Moreover, the organisation and administration of these multi-party democratic elections will be closely watched by political parties, the media, and international election observers. The continent’s political landscape has changed dramatically since the 1990s, with many, if not all, countries on the continent now in support of multi-party and competitive elections.

However, it is clear from Africa’s first general election of the year – Nigeria – that elections still take place under very difficult conditions. The delayed election held on 23 February 2019 revealed that election management continues to be a very complex administrative operation which has to be implemented within a very volatile political and security atmosphere.

Contributing to this state of affairs are the actions of rogue domestic and foreign actors with self-seeking motivations, trying to discredit the process. This has led to a lack of credibility and public confidence in both the electoral process and the outcomes. The contested political and security character of elections in Africa varies widely depending on the phase of the country’s political development. For example, South Africa since 1994 is touted as one of the few African countries that hold legitimate, free and fair municipal, provincial and national elections.

Post-election, it is rare for the losing political parties to challenge the conduct of the election or its outcomes. The Independent Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC) has high levels of integrity to ensure fair and equitable access to all contesting parties and candidates, whereas in other African countries, election rigging, violence and annulment remain common practices. This is because unlike South Africa, there is a lack of public confidence and integrity in the electoral management bodies. The lack of autonomy of some of these organisations from government influence and control continues to be one of the major challenges. However, we are beginning to observe the role of the constitutional courts in validating the processes and outcomes.

Despite these developments, the supreme or constitutional court rulings on accusations of election fraud, calls for recounting of ballots and rejecting outcomes are often dismissed by opposition parties. The issue of election management bodies’ independence has become a central focus in Africa.

However, the issue is not with these organisations, or how they conduct the election or the existing electoral system, but the electoral process. The terms “election”, “electoral system” and “electoral process” are often communicated as synonymous, but these concepts/terms/phrases do not mean or refer precisely to the same phenomenon. Election refers to a single activity or event which often occurs on a particular day(s) and time(s) involving the selection of particular parties or candidates by millions of citizens in different areas across the country.

Although there are different organisational approaches to the design and conduct of elections on the continent, there are many common themes and issues faced by all African countries, which is electoral administration. In many cases, this originates from the electoral system and process. The electoral system is a set of rules or laws that govern how elections are to be conducted and how results are to be determined, whereas an electoral process involves a series of activities spread over days, weeks, months and years prior to and post-elections.

The electoral process is a multi-level, multi-dimensional, multi-faceted, top- and bottom-up process which is anchored on the agency and inventiveness of many state and non-state stakeholders at local and national governance. All the challenges associated with the management of the largest single activity that span across the length and breadth of a country in both rural and metropolitan areas involving millions of citizens going to the polls emanate from the electoral process.

Elections are part of an ongoing, long-term and multi-stakeholder (eg CSOs, political parties, and NGO) commitment to establish interdependent, interconnected and inclusive democratic institutions. And part of these democratic systems is the development of an ethical, competent and autonomous electoral management body mandated and protected by the constitution with the freedom of action to create institutions, foster norms, attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours that accept equal political participation and tolerate multi-party competition. This is a long and multidimensional process that involves political will from all political parties and civil society organisations.

At present, there is a growing international consensus that there is no universal and perfect model for conducting elections and many countries, including the United States, are calling for electoral reforms. However, there are universally accepted “norms” and “principles” that have to be met in order for an election to be regarded as credible and transparent. As a result of the dissimilarity in electoral laws, rules, regulations and procedures across the African continent, the electoral processes will not be the same. They should be seen as a continuous process of “learning by doing” as a country discovers what works within their national environment.

African countries’ diverse and distinctive changing social environments requires that they (re)think and (re)imagine context-sensitive electoral reforms. The electoral process should be seen as a process of experimentation, learning and correction rather than an exporting of a Western ‘size-fits-all’ process of design, planning and implementation. All electoral process developments have gone through different phases with political changes, and Africa should not be an exception. Irrespective of elections not being the only defining feature of liberal democracies, their success or absence primarily determines and defines the legitimacy (or lack of) the political authority.

At present, there are irregularities in the management of elections in some African countries that require reform. African countries have to acknowledges the complexity of the electoral process endeavour.

There should be a holistic understanding of the electoral process where different parts of the process need to be articulated in a complementary manner. Election management bodies are constitutionally mandated to administer electoral activities such as polling, counting of votes, registration of political parties, campaign finance, a design of the ballot papers, drawing of electoral boundaries, resolution of electoral disputes, civic and voter education, and media monitoring.

The “electoral process” is an ongoing, long-term, multi-stakeholder, bottom-up and top-down commitment by the diverse community of state and non-state actors to engage in collaborative problem-solving and dialogue on electoral design, planning and implementation.

Originally Published by Daily Maverick written by Michael Khorommbi

DM

African Democracy Coming of Age

In this special coverage of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we profile SDG 16, whose aim is to promote peaceful and inclusive societies, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. We look at how African governments are handling corruption, electoral systems, the media, the judiciary and how they are engaging civil society.

Development experts sum up the solution to Africa’s socioeconomic and political problems in two words: good governance. If Africa’s 54 countries practice good governance, these experts say, their economies will grow, poverty will be eliminated and the continent’s 1.2 billion people will enjoy prosperity.

Accountability, transparency, responsibility, equity and the rule of law are some of the characteristics of good governance, according to the UN.

The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), an instrument established by the African Union (AU) to promote political stability, economic growth and integration on the continent, explains what good governance entails. It begins with national constitutions reflecting the ideals of democracy.

Endless journey

Another aspect of good governance, according to the APRM, is effective electoral bodies that conduct free and fair elections, follow the rule of law and are pledged to accountability, separation of powers (particularly judicial independence) and the rights of women, children and vulnerable groups, including displaced persons and refugees.

Elements of good governance as described by the APRM and the UN are largely aspirational, which makes it difficult to identify fully when a country achieves good governance. Countries are tested by a self-assessment questionnaire. “Good governance is an ideal which is difficult to achieve in its totality… Very few countries and societies have come close to achieving good governance in its totality,” says the UN.

What that means is that most countries can only strive to practise good governance. The UN, the World Bank, the AU and other bodies encourage countries and citizens to begin a good governance journey, and many organizations, such as Transparency International (TI), the World Bank and Afrobarometer, periodically measure distances covered.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development launched by the UN in September 2015 also concentrates on good governance. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16, for instance, focuses on the promotion of just, peaceful and inclusive societies, while SDG 5 calls for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Also, the AU’s Agenda 2063, a roadmap that emphasizes the importance to success of rekindling the passion for pan-Africanism—a sense of unity, self-reliance, integration and solidarity that was a highlight of Africa’s triumphs of the 20th century—consists of a set of seven aims, anchored on good governance, to transform the continent’s socioeconomic and political fortunes within 50 years.

Agenda 2063 Aspiration 3 envisions an “Africa of good governance, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law,” while Aspiration 6 envisions “an Africa whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children.”

Most governments tout their policies as geared towards good governance the policies are then evaluated by TI and other organizations to determine if actions match words.

Measuring performance

Transparency International’s 2015 index based on a corruption perception survey ranked Botswana as Africa’s best performer, at 28 out of 167 countries, followed by Cape Verde at 40. The poor performers were Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Angola, Libya and Guinea-Bissau.

Conflict countries performed poorly, which suggests that conflicts affect good governance practices. However, the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) differs with TI over the latter’s use of “perception” as an indicator of corruption. “No single indicator of corruption should be used,” says Carlos Lopes, the ECA’s executive secretary, in a foreword to the 2016 African Governance Report IV.

Assessments of corruption in Africa should also include information on the activities of international players involved in asset repatriation and money laundering, Mr. Lopes says.

Another watchdog instrument is the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, an annual assessment of the quality of governance in Africa. It consists of more than 90 indicators built up into 14 subcategories, four categories and one overall measurement of governance performance.

Its 2015 report ranked Mauritius as Africa’s best performer, followed by Cape Verde, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Seychelles and Ghana, in that order. Somalia, again, ranked the lowest, below South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Sudan.

Mauritius shows a connection between good governance and economic development. Globally, Mauritius is ranked 32 out of 189 countries in Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency, a flagship World Bank report.

In 2013 Mauritius confirmed its reputation as an investment destination when it became the highest-ranked sub-Saharan African country on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, having overtaken South Africa. The country even has a Ministry of Financial Services, Good Governance and Institutional Reforms that fights fraud and corruption and promotes good governance.

Tempering this positive picture is the charge leveled by the charity ActionAid that Mauritius is a tax haven for illicit financial flows.

Some African countries have posted impressive data on citizens’ political participation, especially women’s. With 51 out of 80 parliamentary seats occupied by women (63.8%), Rwanda leads the world in women’s parliamentary representation, according to a 2015 report by the Inter-Parliamentary Union, a global organization of parliaments. Senegal comes fifth on the global scale, with women occupying 64 out of 150 seats (42.7%).

Democracy is the foundation of good governance, notes the AU, which, along with regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), denies membership to undemocratic countries. After a military coup in Mali in March 2012 and in Guinea-Bissau a month later, ECOWAS suspended both countries’ membership in the regional community.

Despite setbacks in Mali and Guinea-Bissau, a 2012 study by the African Development Bank (AfDB) showed a decline of up to one-third in coup attempts in Africa. In the study covering the periods 1970–1989 (99 coup attempts) and 1990–2010 (67 coup attempts), the AfDB attributed the decrease —which can be interpreted as an increase in democratic practices—to a vocal civil society (particularly the involvement of young people and the middle class), a changing international environment (as foreign countries have less interest in Africa’s domestic affairs), and pressure from regional groupings such as ECOWAS (which has the power to impose sanctions on military regimes).

The journey continues

Nevertheless, a lack of free and fair elections can heat up domestic politics, often leading to violence. “Flawed elections, when passed as free, fair and credible, leave citizens with little choice than to agitate for regime change,” writes Emma Birikorang, a senior research fellow at the Accra-based Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, in an article titled “Coups d’état in Africa: A Thing of the Past?” The training centre conducts research and training in conflict prevention, management and peacekeeping.

Rigged elections often entrench incumbents in countries where democracy is under attack. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s series of Democracy Index reports, published by The Economist, a UK-based publication, assesses countries on “electoral processes and pluralism, civil liberties, the functioning of government, political participation and political culture.” It categorizes governments in four groups: full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes and authoritarian regimes.

Full democracies score high on good governance practices, particularly civil liberties and free and fair elections. Flawed democracies consist of relatively free and fair elections but are characterized by low political participation and

a weak political culture. Hybrid regimes may conduct elections but fall short on civil liberties, while authoritarian regimes have sit-tight leaders with no interest in elections.

Mauritius was the only African country with full democracy, according to Democracy Index 2015. Countries listed as hybrid democracies included Benin, Botswana, Cape Verde, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. The majority of African countries were categorized as authoritarian.

In 2015, elections were held in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zambia that were seen as relatively peaceful, free and fair. In Nigeria, there was a smooth handover of power when the opposition All People’s Congress defeated the ruling People’s Democratic Party, marking the first time an opposition party unseated a ruling party in the country’s history. But a controversial constitutional amendment in Burundi allowed President Pierre Nkurunziza to get a third term, plunging the country into crisis.

In Ethiopia, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn’s People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front reported a 100% victory, capturing all the 546 parliamentary seats. Africa’s 2016 electoral calendar includes the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Niger, Somalia, Uganda and Zambia. Successful elections could boost good governance in these countries.

Overall, Africa’s good governance picture shows steady progress, despite hiccups. Data generally indicates that good governance is trending in the right direction. The AU, the ECA, regional economic groupings and many governments recognize that citizens are

yearning for good governance, and are responding with appropriate policies, as shown by the continental adoption of Agenda 2063.

As well, vocal civil society organizations are holding authorities accountable. The judiciary, media, electoral bodies and other institutions are helping to strengthen good governance in many countries, even if under pressure to do better.

One can say with a degree of certainty that Africa is on a slow but steady march forward.

African democracy coming of age

Written By: Kingsley Ighobor

https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/august-2016/african-democracy-coming-age

Space Desk Workspace Coworking

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged.

Contrary to popular belief, Lorem Ipsum is not simply random text. It has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source.

All the Lorem Ipsum generators on the Internet tend to repeat predefined chunks as necessary, making this the first true generator on the Internet. It uses a dictionary of over 200 Latin words, combined with a handful of model sentence structures, to generate Lorem Ipsum which looks reasonable.

There are many variations of passages of Lorem Ipsum available, but the majority have suffered alteration in some form, by injected humour, or randomised words which don't look even slightly believable. If you are going to use a passage of Lorem Ipsum, you need to be sure there isn't anything embarrassing hidden in the middle of text.

Food Salad Restaurant Person

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged.

Contrary to popular belief, Lorem Ipsum is not simply random text. It has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source.

All the Lorem Ipsum generators on the Internet tend to repeat predefined chunks as necessary, making this the first true generator on the Internet. It uses a dictionary of over 200 Latin words, combined with a handful of model sentence structures, to generate Lorem Ipsum which looks reasonable.

There are many variations of passages of Lorem Ipsum available, but the majority have suffered alteration in some form, by injected humour, or randomised words which don't look even slightly believable. If you are going to use a passage of Lorem Ipsum, you need to be sure there isn't anything embarrassing hidden in the middle of text.

Pink Petaled Flower Near White Ceramic Plate

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged.

Contrary to popular belief, Lorem Ipsum is not simply random text. It has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source.

All the Lorem Ipsum generators on the Internet tend to repeat predefined chunks as necessary, making this the first true generator on the Internet. It uses a dictionary of over 200 Latin words, combined with a handful of model sentence structures, to generate Lorem Ipsum which looks reasonable.

There are many variations of passages of Lorem Ipsum available, but the majority have suffered alteration in some form, by injected humour, or randomised words which don't look even slightly believable. If you are going to use a passage of Lorem Ipsum, you need to be sure there isn't anything embarrassing hidden in the middle of text.

Vegetables Shopping Basket Close Up

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged.

Contrary to popular belief, Lorem Ipsum is not simply random text. It has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source.

All the Lorem Ipsum generators on the Internet tend to repeat predefined chunks as necessary, making this the first true generator on the Internet. It uses a dictionary of over 200 Latin words, combined with a handful of model sentence structures, to generate Lorem Ipsum which looks reasonable.

There are many variations of passages of Lorem Ipsum available, but the majority have suffered alteration in some form, by injected humour, or randomised words which don't look even slightly believable. If you are going to use a passage of Lorem Ipsum, you need to be sure there isn't anything embarrassing hidden in the middle of text.

Food Kitchen Cutting Board Cooking

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged.

Contrary to popular belief, Lorem Ipsum is not simply random text. It has roots in a piece of classical Latin literature from 45 BC, making it over 2000 years old. Richard McClintock, a Latin professor at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia, looked up one of the more obscure Latin words, consectetur, from a Lorem Ipsum passage, and going through the cites of the word in classical literature, discovered the undoubtable source.

All the Lorem Ipsum generators on the Internet tend to repeat predefined chunks as necessary, making this the first true generator on the Internet. It uses a dictionary of over 200 Latin words, combined with a handful of model sentence structures, to generate Lorem Ipsum which looks reasonable.

There are many variations of passages of Lorem Ipsum available, but the majority have suffered alteration in some form, by injected humour, or randomised words which don't look even slightly believable. If you are going to use a passage of Lorem Ipsum, you need to be sure there isn't anything embarrassing hidden in the middle of text.

© Copyright 2025 Africa Democracy and Governance by #AfricaDemocracy